What “Counts” as a Mathematician?

The “Best Job” of 2014 #

A few days ago the website CareerCast (Adicio, Inc) released a list of the top jobs in 2014 which put “Mathematician” as number 1. Most news sites have used this as a platform to discuss the centrality of mathematics and technology in the world economy, or the importance of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) in education. I’m not against such discussions — indeed I spend a large fraction of my time writing long and detailed posts explaining mathematics to anyone who will listen — but I do suspect the ranking is misleading.

As every mathematician knows definitions are extremely important, so I wonder how mathematician is defined for the purpose of this ranking. After a bit of snooping it appears at least part of their analysis comes directly from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics website, which in turn uses an aggregation of two occupational classification models.

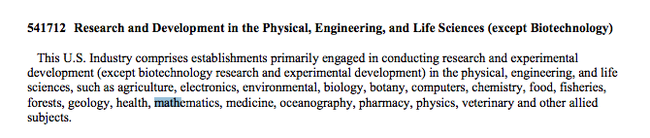

The first is the North American Industry Classification System, which has no record solely for a mathematician. The closest they get is the following

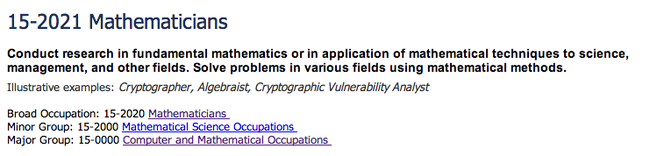

The second source, the 2010 Standard Occupational Classification is more useful. They distinguish between a variety of mathematical fields, but still give no information about how the data was collected for any occupation. Mathematicians just has a list of examples that are clearly biased:

But on the other hand the major group category gives some more pleasing discriminations, such as operations research analyst and “mathematical technician” (which I think is a wonderfully useful category).

The search hits a dead end here, because neither does the Census Bureau or the Bureau of Labor Statistics state how they determined their statistics from the classification (Did they use job title? Did they ask the people surveyed what they consider themselves?) nor does CareerCast state how they aggregated their 200 jobs out of the 500+ jobs that the BLS aggregated statistics for.

Mathematicians also have an odd place in a survey of occupations because mathematics is so intertwined with other disciplines. Two people with the same job title (say, “Security Expert”) could have different enough jobs that one is a mathematician while the other isn’t. Indeed, even the Bureau of Labor Statistics agrees,

Most people with a degree in mathematics or who develop mathematical theories and models are not formally known as mathematicians.

So the question is what counts as a mathematician? Or better, since nobody has seemed to ask this question: what should count as a mathematician? I’ll give my answer with a few examples to ramp up to my final answer. I want to preface my examples with a large and bold claim: I am not making a value judgement either about mathematician’s being good or other jobs being bad. I like being a mathematician, but I don’t consider people in mathematical fields (who I don’t consider mathematicians) to be lesser in any way. I am simply trying to come up with a well-defined (if somewhat informal) classification rule that aligns with my idea of what a mathematician is. So here it goes.

Examples and a Definition #

I don’t consider an actuary to be a mathematician (and I’m glad to see that CareerCast appears to agree). Actuaries certainly need to know and use a lot of mathematics in what they do; they manage risk and risk is naturally mathematical. But they use mathematics as opposed to doing mathematics.

In the same vein, many data scientists are not mathematicians. Why? Because despite their analytical skills and statistical know-how, data scientists largely apply known statistical and machine learning models as black boxes to their data sets. This of course depends on the scientist, and there are many critics of posers in the land of data science. As Cathy O'Neil puts it:

My basic mathematical complaint is that it’s not enough to just know how to run a black box algorithm. You actually need to know how and why it works, so that when it doesn’t work, you can adjust.

I would take this even farther: a data scientist should not be considered a mathematician unless their job requires them to significantly modify standard models and algorithms to suit their needs. Even better, they should be creating new models.

More generally, I can now make the following definition of a mathematician.

Definition: A mathematician is someone who, as part of their occupation, devotes a nontrivial portion of their time to the invention of new mathematics.

“Inventing new mathematics” also requires a definition, and I would consider it to be one of the two following things:

- Any original model, algorithm, problem, heuristic, or mathematical definition.

- An original theorem, proof, conjecture, or analysis pertaining to one of the above.

One might protest: nothing can truly be original anymore! I don’t mean to use original in the sense that something has never been done before, but that it is something that you have never seen or done before. You cannot be called a mathematician if your “new model” is knowingly (by you) and trivially derivative of someone else’s work. You cannot be called a mathematician if you use or implement someone else’s algorithm. You can be called a mathematician if you prove the correctness or efficiency of an algorithm. This is regardless of whether the algorithm is widely known, considered interesting or important, or even whether an identical analysis was done in the 70’s. All that matters is whether you’re the one producing original mathematics.

This extends to invalidate typical measures: you are not a mathematician just by having a mathematical publication, nor are you not a mathematician if you have no publications. But if you publish regularly in mathematical journals or conferences, then you are a mathematician.

As a thought experiment to illustrate my point, say you were being paid, as an occupation, to reinvent basic geometry while you were devoid of contact with the outside world. You might spend much of your time puzzling over trivial facts taught in high schools every day, and you might come up with definitions and theorems that are wholly worse than Euclid’s. But you are still a mathematician.

The finer point is that doing mathematics is equivalent to inventing mathematics. That’s why I think the classification “mathematical technician” is such a wonderful category: it gives a name to the people who apply standard techniques to solve problems that don’t require new mathematics. They are the engineers, financial analysts, and operations researchers using satisfiability-solvers to optimize their chip designs and Black-Scholes to price their options.

A perhaps displeasing consequence for mathematicians hoping to keep the #1 spot on that list is that this definition declares graduate students in mathematics to be mathematicians. And I would argue this is rightly so: the purpose of a PhD program is to induct one into the research community as a peer. So the second you start trying to tackle original problems is when you don the title of mathematician. (Fair disclosure, I am a PhD student in mathematics)

The unfortunate part is that the median salary of a graduate student is quite low. Many, including myself, make roughly the federal minimum wage. Considering that mathematics PhDs take 4-6 years and that drop-out rates are nontrivial and career switches are common (many PhDs end up teaching without inventing any new mathematics), it seems deceitful not to factor that into the analysis.