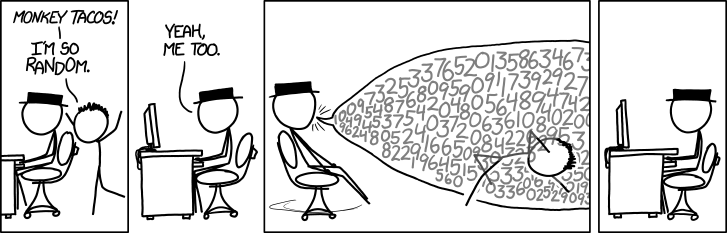

How can you tell what’s random?

A handful of really deep concepts in mathematics come from the attempt to give a formal answer to a simple question: what does it mean for something to be random?

The short answer is: we have multiple ways to understand what randomness means, but nobody knows an effective way of deciding what’s random and what’s not random.

Even with the string of digits in the above comic, how can we really tell that they’re random? Certainly they aren’t. Randall Munroe deliberately chose numbers and their placements to make it appear random (unless he flipped coins or something, which I doubt), but how can we verify or refute the claim that they’re random? Without an answer, the comic becomes doubly-ironic: it’s just describing how our perception of the meaning of randomness changes, based on age or intellectual maturity or whatever.

But before we can check whether something is random, we have to decide what being “random” even means! And it turns out there are many different ways to define randomness.

The first is via statistics. If you want to decide whether a sequence of numbers is random, you run a bunch of statistical tests on it and if they all say it’s random then you say it’s random. The problem with this approach is that it simply doesn’t work. There are too many simple patterns that bypass statistical tests, and you never can be sure you’ve picked enough tests. See for example this page on “cheap” not-so-random number generators. But nevertheless, statistical testing is a huge research field and for good reason: even though defects might not occur randomly, running statistical tests to determine the quality of manufactured goods is extremely effective.

The second way to define randomness is via Kolmogorov complexity. In brief, the Kolmogorov complexity of a (finite) list of numbers is the length of the shortest program that outputs those numbers. We then call a sequence “random” if its Kolmogorov complexity is at least the length of the string of numbers itself, in which case the shortest program is just to embed the sequence of numbers verbatim in the program. This might sound really nice, but there is a huge problem: Kolmogorov complexity is impossible to compute. Not impossible as in inefficient or infeasible. Impossible as in there cannot logically exist a program which computes the Kolmogorov complexity of its input string. This kind of impossible is known as uncomputable or undecidable. It might be shocking that certain things are provably impossible to compute given infinite time and space, but it’s true, and figuring out what sorts of things can and can’t be computed is the domain of theoretical computer science (my research field).

The third way is via cryptography. In cryptography they call a function (say, a function which generates an integer sequence) pseudorandom if it can’t be distinguished from a truly random function in polynomial time. That is, it’s random if there is no program which, when given black-box access to both your function and a random function (and doesn’t know which is which), cannot pick the pseudorandom one with probability much better than guessing.

This is the big distinction that cryptographers rely on: not that it is impossible to tell the difference, but infeasible to do so with high probability and a polynomial time budget. In other words, if you’re pseudorandom then it’s as good as random for the purposes of any mere mortal.

Some of the biggest open conjectures in theoretical computer science concern this very idea, since no pseudorandom functions are even known to exist! They are all roughly the consequence of the existence of one-way functions. But again, as of today there’s no known procedure to tell if a sequence is even pseudorandom, because if there were we’d probably be able to find a truly pseudorandom function and resolve these open problems.

So in a quest to define randomness it all boils down to this: we have lots of ways of understanding what randomness might mean, but nobody has an effective way of deciding what’s random and what’s not random. If you think of one, let me know :)